Peter Townson, Professor Marek Kowalkiewicz, 4 April, 2021

You’re smiling as your e-scooter whispers along the riverside path. Without the helmet, the wind can blow through your hair – and it looks good! You hear a shout, “Pull over!”, and turn to see police heading towards you with your helmet in hand.

Police conducted a blitz on safety breaches by electric scooter riders in Brisbane over the weekend. And employees of operator Lime tell us safety issues have been persistent in Australia’s first trial of a shared e-scooter scheme.

How do we educate users about helmets and safe riding behaviour? And how can helmets be distributed cost-effectively?

As with other disruptive tech companies with mass appeal, the safety and regulatory issues raised by e-scooters – including rider and pedestrian safety and being left in inappropriate places – are attracting attention. A closely related issue is helmets and their role in rider safety.

Scooter operators have come under pressure to encourage riders to wear helmets. The RACQ has called on Lime “to ensure every scooter put out has a helmet attached”.

A day in the life of a helmet

Ultimately, responsibility for public safety and compliance with civic cleanliness rests with the individual mobility provider. Lime accepts this and has announced it will distribute 250,000 helmets worldwide.

Each day fully charged scooters, with helmets, are placed on footpaths. At the end of each day, the tally of scooters and helmets does not add up. This is known in the industry as helmet churn – the constant loss and replacement of helmets. Unlike the scooters themselves, which have smart tracking technology, helmets are kept cheap to minimise the cost of these losses.

Let’s try to unpack the issue of helmet churn.

It is agreed that not wearing a helmet plays a part in the problem. Some riders simply leave it behind. Aside from being unsafe, this separates the helmet from the scooter, so it becomes unavailable for the next scooter user.

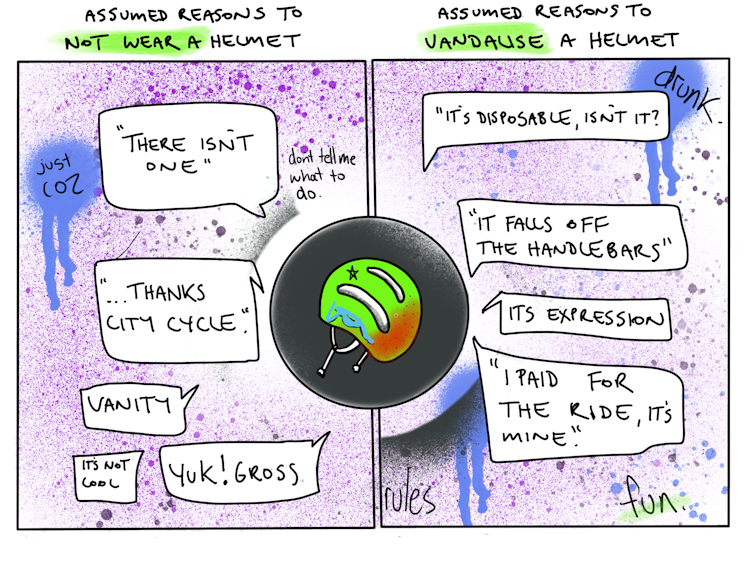

New insights are emerging as we begin to study this phenomenon. Reasons for helmet churn are linked to a reluctance to share them – we believe some riders worry about hygiene – and it being a disposable product. It seems there may even be feelings of ownership, with some perceiving the helmet to become their property through paying for the ride.

Peter Townson/QUT Chair in Digital Economy

Limits of deterrence

Two main compliance mechanisms are in place to discourage riders from contributing to helmet churn: police and Lime.

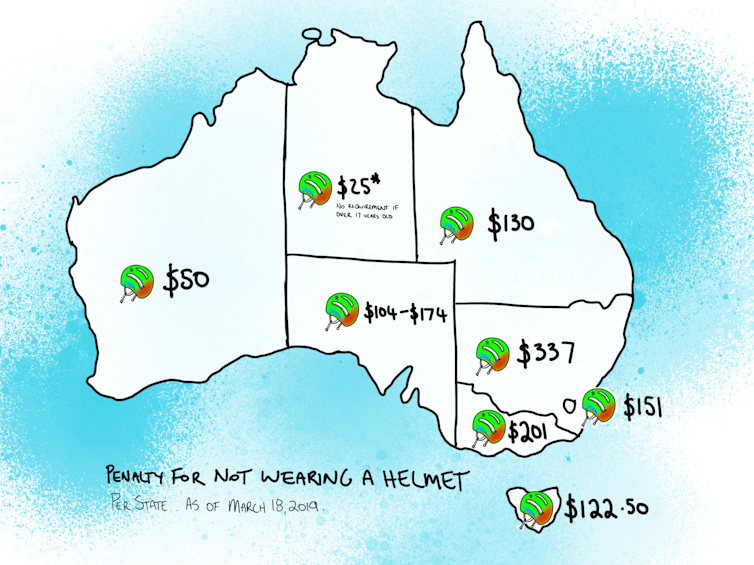

In Queensland, the fine for not wearing a helmet is A$130. In other states and territories fines range from as little as A$25 to as much as A$337.

Research into deviant consumer behaviour tells us this tactic of appealing to fear of punishment extends only to riders wearing helmets. It does not have an effect on the broader issues of vandalism and theft.

Peter Townson/QUT Chair in Digital Economy

The research also suggests the “fear of punishment” approach makes two critical assumptions:

- that people agree the behaviour is wrong (“yes, this is dangerous”)

- riders think there is a real risk of being caught (“catch me if you can”).

Given this is not always the case, a risk-based approach to deterrence is limited.

Lime also plays a part in curbing helmet noncompliance. Its current strategy, aside from providing the helmets, is the Respect the Ride education program. It aims to foster a community and culture of safe mobility, underpinned by a personal pledge each rider is encouraged to make.

This approach is appropriate for trying to change the behaviour of not wearing a helmet. It does not target people who are taking advantage of publicly available helmets.

These measures still do not fully solve a pervasive problem.

You have a disruptive mobility company in the spotlight because of safety concerns. The company has a duty of care to supply helmets and ensure riders are safe. Riders are disregarding, disposing of, defacing and destroying helmets.

How do we solve this tough, intractable, social problem?

A shift in thinking – ecosystem view

If helmet churn exists for Lime scooters, then it exists for all other ride-share operators in that area. If a helmet isn’t available, riders will often borrow from other services such as share bikes.

Helmets are sometimes considered “free for grabs” across different mobility providers. Should the duty of care that requires helmets be provided rest on each mobility service operator, when the noncompliance of one undermines them all?

While these personal transport providers are in competition with one another, they have an opportunity to relinquish their individual burden of helmet churn by working together on the problem.

A shift in thinking – personalised view

If the one constant across various mobility services is the rider, we should also consider a “bring your own helmet” approach. This approach possibly started in technology companies (“bring your own device”, allowing employees and customers to use their own devices to interact with an organisation) and has spread to other areas. For instance, environmentally conscious coffee lovers bring their own cups, while still having the option of using a paper cup.

Could a similar option work for helmets? Disposable helmets – made of cardboard – are being tested as a concept. And personalised helmets that look and feel like a beanie can be pre-purchased from a start-up created by QUT students.

Cyclists still carry their own helmets when they commute on their own bikes, so the acceptance of this BYO approach should be simple. The difference is users need only provide a helmet, without having to worry about finding safe parking and storage places for the day or overnight.

Adapting to disruption

The meaning of a helmet has shifted significantly from individual property to a shared utility, as has the meaning of many modes of transport, including bikes and scooters. There are two paths from here: ecosystem, with ubiquitous helmets available for everyone; and personalised, with riders bringing their own helmets.

Either of these is different from the world we know today. The bigger picture is a collaborative effort to achieve the goal of rider safety.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.