Professor Gary Mortimer, 25 October, 2021

Australia’s federal agriculture minister, David Littleproud, has called for a boycott of supermarket-branded milk. He is angry about lack of support for a “milk levy” of 10 cents a litre wanted by the dairy industry to support drought-stricken farmers.

Fellow National Party colleagues have called for nothing less than a royal commission into the supermarkets’ support for farmers. Nationals leader, and deputy prime minister, Michael McCormack, has said he is open to the idea.

Amid intense price competition across many supermarket categories, the price of milk stirs passions like nothing else.

But calls to boycott supermarket-branded milk are misguided; and a royal commission would not be money well-spent.

The widely held belief that supermarkets are hurting dairy farmers by driving down the price of milk is incorrect.

It overlooks basic supply chain dynamics and the findings of the 18-month-long inquiry by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, which was ordered by then federal treasurer Scott Morrison to investigate the low milk prices paid to dairy farmers.

Indirect relations

Looking at the supply chain for fresh milk helps show why the retail price of supermarket-branded milk does not determine the price paid to farmers as some claim.

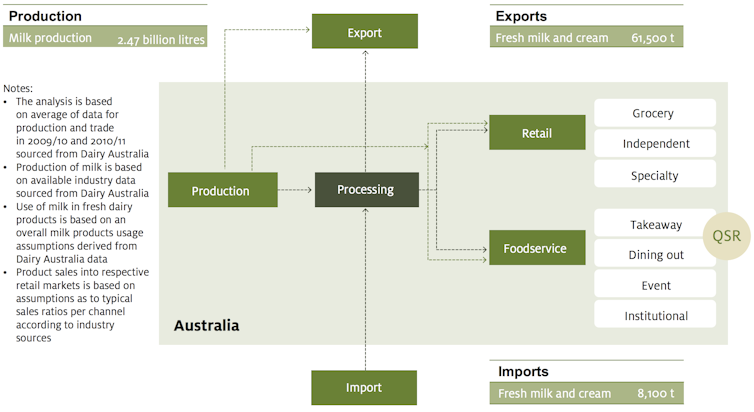

There are many players within a food supply chain: producers, processors, wholesalers, retailers and consumers.

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

Dairy farmers typically sell their milk to processors, who then sell to supermarkets. There is a relationship between the supermarket and processor, not supermarket and farmer. Whether the supermarket sells a litre of milk at $2, $3 or $4 has no direct relationship on the price the processor pays to the farmer.

In the words of the final report of the competition watchdog’s Dairy Inquiry, “the farm-gate price paid to farmers for milk used to fulfil private label milk contracts is not directly correlated with private-label milk retail prices”.

Blame dairy processors

The ACCC’s report does identify a range of market failures due to bargaining power imbalances and information asymmetry, but these are crucially between dairy farmers and processors.

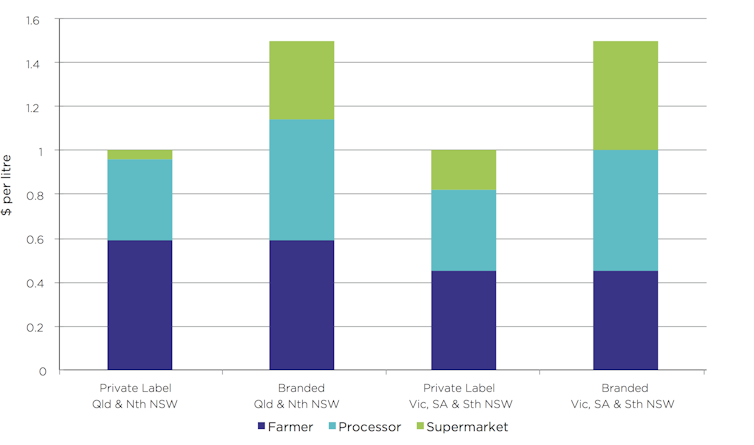

Dairy farmers’ weak bargaining power means any higher price paid by supermarkets to processors would not necessarily result in higher farm-gate prices. The ACCC report notes that farmers get no more money for the milk that is sold at higher retail prices (such as branded milk).

Processors, not supermarkets, set farm-gate prices in response to market conditions (global and domestic demand), at the minimum level required to secure necessary volumes. Farmers are not paid according to the type or value of the end product their milk is used in. They are paid the same price for their raw milk regardless of what brand goes on the container.

ACCC Dairy Inquiry

Also blame consumers

Supermarkets are under pressure to keep food prices low, particularly on staples such as bread, milk and eggs. This is evident from the fact that campaigns to get shoppers to exercise their power as ethical consumers quickly run out of steam.

In April 2016, for example, national attention on the plight of dairy farmers led to a campaign encouraging shoppers to leave “supermarket branded milk” on the shelves. In a single month the supermarket brands’ share of milk sales dropped from 66% to 51%. Then it began to rise again. Within a year it was back to nearly 60%.

Adding to confusion

While a milk levy to directly help farmers during the drought has many supporters, the disconnect within the supply chain means it is near impossible for retailers to pass the money directly to the intended beneficiaries. That, again, depends on those who buys the milk from the farmers – the processors.

Despite this, and because the ACCC inquiry’s findings have so far done little to dispel myths about the price of milk, retailers such as Woolworths have seen it as prudent to embrace the levy idea and publicly demonstrate support for dairy farmers.

All the additional proceeds from its “Drought Relief” milk go back to processor Parmalat, who is responsible for distributing the money to suppliers in drought-affected areas. Coles, meanwhile, has slapped a 30 cent levy on its three-litre milk containers, with the funds going to the Coles Drought Relief Fund.

These measures arguably add to continuing confusion about how the milk market works and the relationship between farm-gate and retail prices.

In the court of public opinion the supermarkets probably had no option but to go along with the charade.

A minister for agriculture, however, should know better.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.