Professor Gary Mortimer, 4 April, 2021

After weeks of speculation, Woolworths has confirmed it will close 30 of its Big W stores in Australia, as well as two distribution centres. This represents about 16% of its 183-strong network.

The obvious culprit, and the one identified by many analysts, is online shopping.

As one industry analyst explained: “The physical department store footprint is likely to continue to shrink as online sales penetration increases further.”

Online shopping is certainly a factor, but it is not the primary reason for Big W’s troubles.

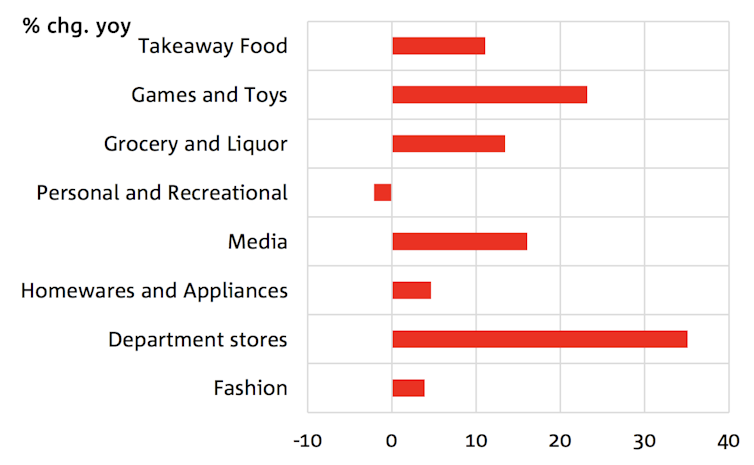

Though online shopping in the department and variety stores category is growing fast (by 29.6% in 2018 according to the NAB Online Retail Sales Index, the total amount of money spent online by Australian shoppers – A$28.8 billion – is still only about 9% of what is spent in traditional bricks-and-mortar stores.

NAB Online Retail Sales Index

More important to Big W’s woes is the growth of the so-called category killers, which are disrupting the entire discount department store business model. It a threat to which Big W has failed to respond with the same agility of rival Kmart.

Departed departments

If you’re old enough you may remember getting your wall paint mixed in the Big W hardware department, or buying car accessories from its automotive department. There was also a large “sight and sound” department filled with televisions, sound systems, videos and CDs. Discount department stores truly lived up to the idea of a variety store.

But the profitability of all these market segments for department stores has been eroded by the growth of “category killers” – retailers specialising in the same product categories.

Examples include Office Works for office supplies, Rebel for sports equipment, JB Hi-Fi for audiovisual, Super Cheap Auto for car parts, and Bunnings for hardware. All have taken market share from the discounters. These stores compete on price and have superior range, and shoppers trust the expertise of staff working in a specialist shop.

Speed of change

The popularity of category killers explains in large part the stagnant sales and talk of store closures throughout the department store segment.

Harris Scarfe and Best and Less are reportedly struggling. The Reject Shop’s net profit for the first half fell from an expected A$17 million to less than A$11 million.

David Jones’ half-year profit fell 39% to A$36 million. Myer reported a 2.8% drop in total sales for the same time frame.

Wesfarmers expects earnings from its department store brands Kmart and Target to fall about 8% this financial year. Eight Target stores closed during the first half of the financial year, with another six closures expected by the end of June.

Cutting losses

Kmart is considered Australia’s discount department store “darling”. A decade ago it was on life support. Under the direction of chief executive Guy Russo it doubled its profits by 2015.

A key to the turnaround was recognition it needed to quickly reduce or exit categories it could not compete in, such as hardware, automotive, fishing, consumer electronics and sporting goods. It has turned to homeware, soft furnishings, manchester and kitchenware.

There appears no such swiftness in Big W’s moves.

Big W’s chief executive from January to November 2016, Sally MacDonald, reportedly wanted to close stores and make other major changes but was thwarted by the board of Woolworths Group, owner of Big W.

Such differences in strategic vision explain why MacDonald left the role within the year.

This process of “right-sizing” therefore seems long overdue. To what extent it makes Woolworths a sustainable business, however, will depend on future response to changing circumstances.

What is certain is that discount department stores aren’t what they used to be; and if they want to be around in future, they probably can’t be what they are now.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.