Clinging to a teddy bear that dwarfs her, Tim Tam takes in her surrounds with shiny-eyed wonder and awe from the safety of her crib.

The five-month-old joey, along with mum Tam Tam, will soon check out from Currumbin Wildlife Hospital, returning home to the idyllic eucalypts of Elanora on the southern Gold Coast.

Hers is a genuine feel-good story.

Weighing just under a kilogram, Tim Tam is among the 34 healthy joeys born through a QUT-led vaccine project.

She represents another small step towards ensuring the long-term survival of koalas in south-east Queensland and along the eastern seaboard.

And she embodies the ‘why’ for Professor Ken Beagley and his passionate colleagues.

The jab that could save a species

Growing up in New Zealand, Ken Beagley did not see a koala, let alone hold one, until he was in his teens.

Fast forward, and koalas would consume his research for the best part of two decades – crucial work which may help save one of our nation’s most beloved species.

Warmly regarded worldwide as cute, fluffy, content creatures, koalas are an iconic attraction for tourists and locals alike. Yet they are under serious threat, both short and long-term.

Chlamydial disease is ravaging a species already fighting survival battles on fronts such as bushfires, habitat loss through land clearing, and food nutrient loss caused by climate change.

There has been a 70 to 80 per cent decline in many populations across Queensland – and localised extinction is a real threat without a chlamydia vaccination. An often-fatal, sexually transmitted bacterial condition, chlamydia also causes infertility, blindness and urinary tract disease. It spreads with devastating effect and antibiotics are not only costly but of limited effectiveness.

Enter Professor Beagley and his QUT-led research team. Working in close collaboration with senior vet Dr Michael Pyne OAM at Currumbin Wildlife Hospital, Ken’s team has developed - and after 10 years in the lab, is now successfully trialling - a vaccine in a localised population on the Gold Coast.

When Professor Beagley and team started treating the small Elanora koala population, rates of chlamydia were around 70 per cent. Three years into a five-year study, about 40 koalas from the Elanora population have been vaccinated, collared and monitored. In a separate study, about 300 animals treated at Currumbin for a variety of conditions have also been vaccinated.

While both studies continue, there are promising outcomes with the majority of those koalas that were chlamydia-free at time of vaccination remaining disease-free at return.

The first QUT-vaccinated koala (named Anne Chovee) has also been released back into the wild, chlamydia-free and having produced a healthy joey.

Professor Beagley says such encouraging results keep him energised towards the long-term goal of a chlamydia-free koala status across Queensland and New South Wales.

His team’s work continues to win recognition and financial support, with substantial contributions from Brisbane City Council and a QUT fundraising appeal moving the next key milestone – registration of the vaccine – a step closer. Registration will enable use by vet clinics and wildlife hospitals throughout the country, without needing the university ethics approval it currently requires as an experimental product.

“We need to do everything we can to help save these iconic marsupials – we want to see healthy koala populations across Australia,” said Professor Beagley. As testing continues, he adds that initial data suggests the vaccine is largely safe, effective and ready to be more widely available.

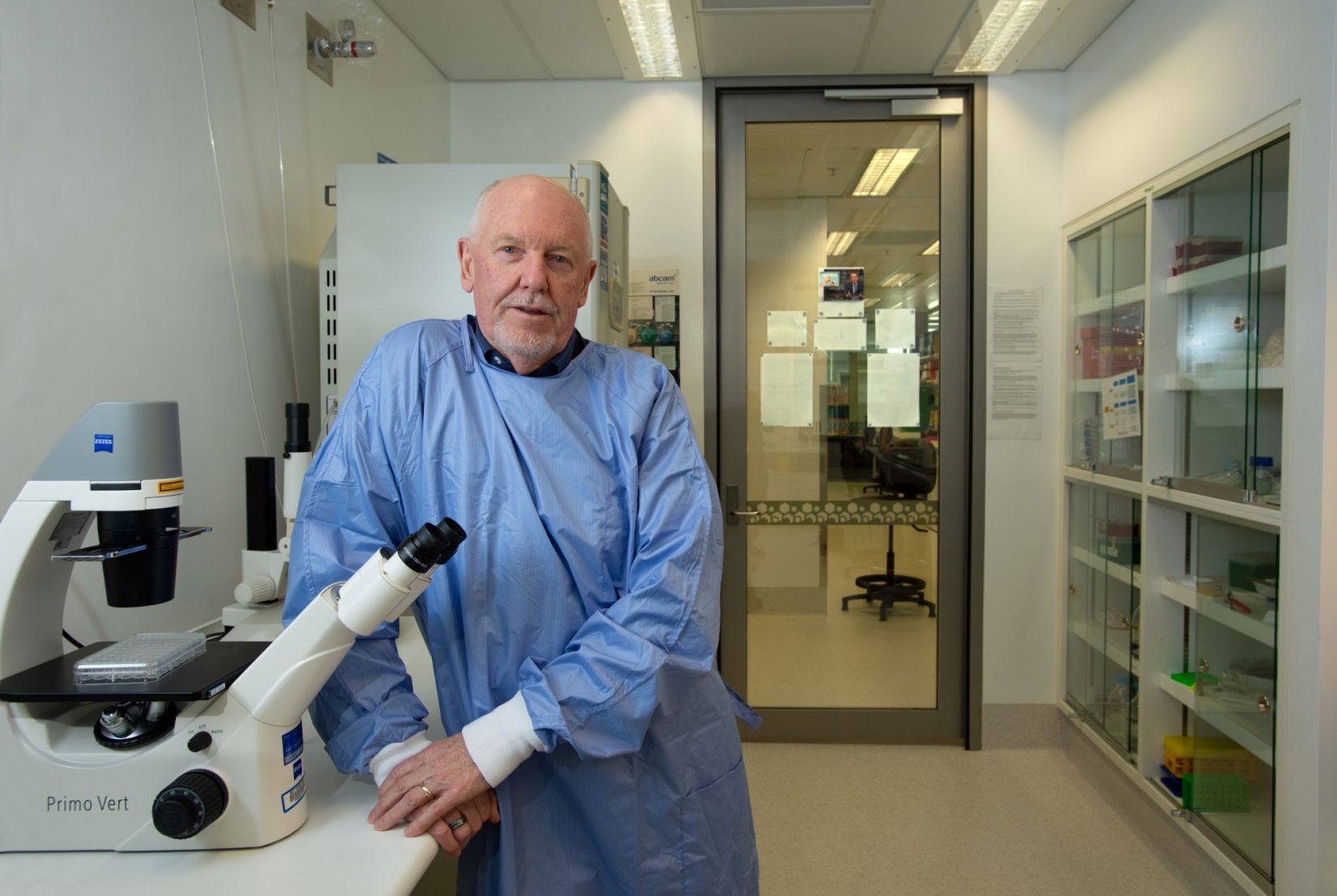

Ken Beagley in the lab

Just like kangaroos, baby koalas are called joeys

Koala with teddy bear

It all started at Currumbin

A high school trip – ironically to Currumbin in 1973 – introduced Professor Beagley to koalas, before a shift in academic institutions years later solidified a burning passion to help.

“They have always been fascinating animals for me,” he said. “(But) I had never seen a koala with chlamydia until I came up here (to Queensland).”

Professor Beagley had conducted early vaccine development at University of Newcastle from 2005 to 2007 but it was only when he moved north to Brisbane, and to the QUT School of Biomedical Sciences, that the life-saving koala research gathered momentum.

“I had been interested in (developing treatments for) chlamydia and other sexually transmitted diseases for a long time,” he said. The work mainly involved mouse models, with the ultimate objective of developing a human chlamydia vaccine.

“By chance, I met the head veterinarian at Lone Pine (koala sanctuary), who was keen on developing a chlamydia vaccine for koalas.

“I soon saw that from Australia Zoo (Sunshine Coast) all the way to Currumbin, chlamydia was a real problem for koalas.

“I had background experience in what was needed for a chlamydia vaccine so at the end of 2007, started the slow process of developing a vaccine for koalas.”

Each koala brought into Currumbin Wildlife Hospital with chlamydia costs about $7,000 to treat, with many staying up to ten weeks due to complications from antibiotics.

It costs Gold Coast City Council about $500,000 per year for the capture-treat-collar-track process, with the QUT and Currumbin Wildlife collaboration also supported by World Wildlife Fund Australia, WildArk, Rotary Currumbin Coolangatta-Tweed and the Neumann Family.

The QUT team aims to capture and immunise 10 per cent of young adult koalas per year from the wild Elanora population, to establish the level of vaccination needed in an infected population to reduce the incidence of chlamydia and improve fertility rates.

Ideally, the real-world impact will convince Gold Coast City Council and the Department of Environment to continue their support after the five-year study ends.

"We hope a repeat survey after five years will show that the majority of vaccinated koalas are disease-free and breeding successfully, with indications the population is starting to recover – then we will no longer need to collar and track the animals,” Professor Beagley said.

“The vaccine is showing signs of success at Elanora. I want to take it to a stage where it can be widely accessed through Currumbin – I want any vet to be able to get it, with the only cost being for a courier and maintaining the ordering website.”

An extra boost to ‘let koalas be koalas’

Professor Beagley’s team has also received federal funding to develop booster implant technology, which would alleviate the need to hold or recapture koalas. Slightly bigger than a pet microchip, it would release a second shot after 30 days and allow in-field vaccination.

“Not having to recapture or hold animals in captivity for a second shot after 30 days is kinder, with less interference … it will let koalas be koalas.”

Key members of Professor Beagley’s QUT team include polymer chemists Professor Tim Dargaville and Dr Kerr Samson, plus Freya Russell (whose PhD project investigated and designed a biodegradable, delayed vaccine delivery device in animals). With expertise in degradable polymers, Professor Dargaville has developed the flexible implant to deliver the booster dose while Dr Samson is fabricating and testing the implants.

Collaborations extend far beyond the Currumbin Wildlife Hospital and QUT researchers. Professor Beagley is also working closely with:

- Jon Hanger and Deidre de Villiers, from Endeavour Veterinary Ecology, on koala management projects

- universities including the University of Queensland (through a close alliance with Associate Professor Steven Johnston) and, internationally, the University of North Carolina – where a National Institutes of Health grant is driving research for a human chlamydia vaccine that has enormous potential to be developed and enhanced in parallel to the QUT koala research.

Professor Beagley hints that he may be counting down to retirement, aligning around the timeframe of the federal booster funding, which runs for 32 months from July 2023. He is looking to mentor the next wave of koala saviours.

“A researcher can’t put their ideas into a nine-to-five job bracket. You never stop thinking about it, there is always that next step to consider,” he said.

“I want to retire knowing I’ve given my best shot to developing a koala vaccine that has shown it works, has been registered, is widely available and is protecting wild koalas.”

Aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

In 2015, UN member states agreed to 17 global Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all.

We believe in the free flow of information

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under Creative Commons licence.