It’s been 230 years since the first convicts arrived in Australia and much has been written of their hardships but very little on what they did for fun. A QUT research project reveals music and dance were integral to their lives as well as good for their health.

- Dancing encouraged by surgeons on convict ships

- Convict life not all floggings and deprivation

- Dancing gave convicts an important social outlet

- Dancing was not illegal but many associated activities were, such as being in unlicensed premises and the breaking of curfews.

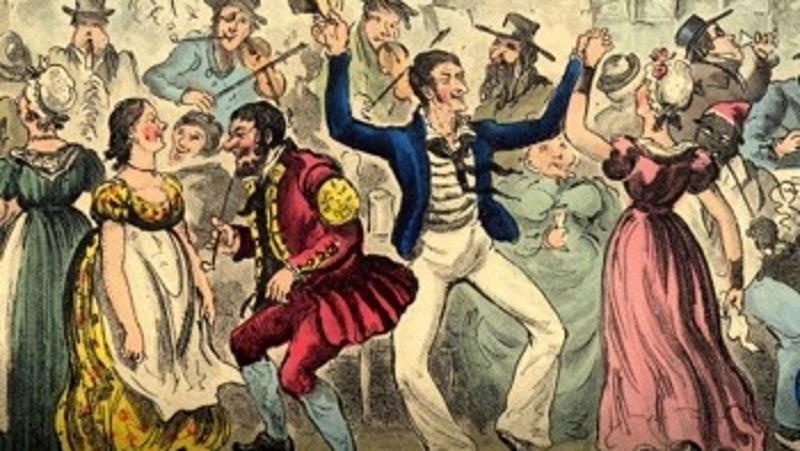

- ‘Lower order’ dancing by convicts and others featured noisy footwork considered bad form in the polite ballroom atmosphere.

Australian colonial dance expert Heather Clarke is completing her Doctorate on the subject of Social dance and early Australian settlement: An historical examination of the role of social dance for convicts and common people in the period between 1788 and 1840.

Her findings will be exhibited at Redcliffe Museum from August to December this year.

“I have always been puzzled at the lack of research, anywhere in the world, regarding dance for the lower echelons of society. The majority of historical research focuses on elite forms of dance – the court, theatre, and ballet,” Ms Clarke said.

“Yet the joy and social benefits of music and dance are universal, whatever your culture or class. For the so-called ‘lower order’ people or convicts, dance was simply a way to enjoy yourself as opposed to being seen in society.

“My research proves that being a convict in Australia was not all about being flogged and leading a miserable existence in some hellish backwater. Many convicts in colonial Australia were in fact better off than those left behind in England’s nightmarish slums.

“Dances were part of the popular culture at ‘two-penny hop shops’ in The Rocks area of Sydney.

“According to newspaper reports, the music for the dancing was supplied by a convict called Jeremiah Byrne from Norfolk, England who played the flageolet (tin whistle). The tunes quoted in one account ('Bobbing Joan', 'Darby Kelly', 'Paddy Ward's pig,' and 'Judy Callaghan) had accompanying dances which had been published in Dublin in the 1810s.

“Most convicts were from Great Britain and many of the dances can be traced to England, Scotland and Ireland while the tunes were often an expression of rebellion.”

Ms Clarke sourced most of her information from police reports of the time and the medical journals of surgeons travelling on the convict ships.

“Dancing was encouraged by many of them. Surgeon James Mercer was on the convict ship Albion in 1823 and wrote: ‘the afternoon of every day was spent in merriment and many exercises such as singing, dancing’,” she said

“Surgeon William Leyson travelled on the convict ship Henry Wellesley in 1837 and noted: ‘I consider that tranquillity of mind is most essential to bodily health....they were allowed to amuse themselves by running about, dancing or in any innocent way whenever the duty of the ship would admit of it.’”

Ms Clarke’s research has shed new light on the life of convicts in Australia. Her project has included a series of workshops to bring the dances to life and retell the story of our early popular culture.

“The notion of convicts having a life which included music and dance is strikingly at odds with the prevailing image of convict heritage,” she said.

“Historians were aware that vernacular culture had quickly become established and then flourished in the English penal colony in Australia, but little was known about social dance practices. We now have a comprehensive and readily accessible database.”

Find out more at Ms Clarke’s website on Australian Colonial Dance. Original material in video courtesy of 4G Productions/David Gilchrist.

Media contact:

Amanda Weaver, QUT Media, 07 3138 3151, amanda.weaver@qut.edu.au

After hours: Rose Trapnell, 0407 585 901, media@qut.edu.au