Netflix is often criticised as a Hollywood-style entertainment behemoth crushing all competition and diminishing local content but a QUT academic says that’s a simplistic view.

- Netflix model a gamechanger for entertainment

- The ‘zebra among horses’ has turned ‘pay TV’ concept on its head

- Unlike old Hollywood, Netflix fosters local content for a global audience

- It’s produced content in more than 28 countries for more than 167-million subscribers worldwide

Media studies expert Professor Amanda Lotz, from QUT’s Digital Media Research Centre, said there is a lot of misunderstanding about the world’s biggest internet-distributed video service.

“Netflix must be examined as a zebra among horses,” said Professor Lotz who is in the middle of a three-year Australian Research Council Discovery Project - Internet-distributed television: Cultural, industrial and policy dynamics. She recently published an article in the International Journal of Cultural Studies - ‘In Between the Global and the Local: Mapping the Geographies of Netflix as a Multinational Service.’

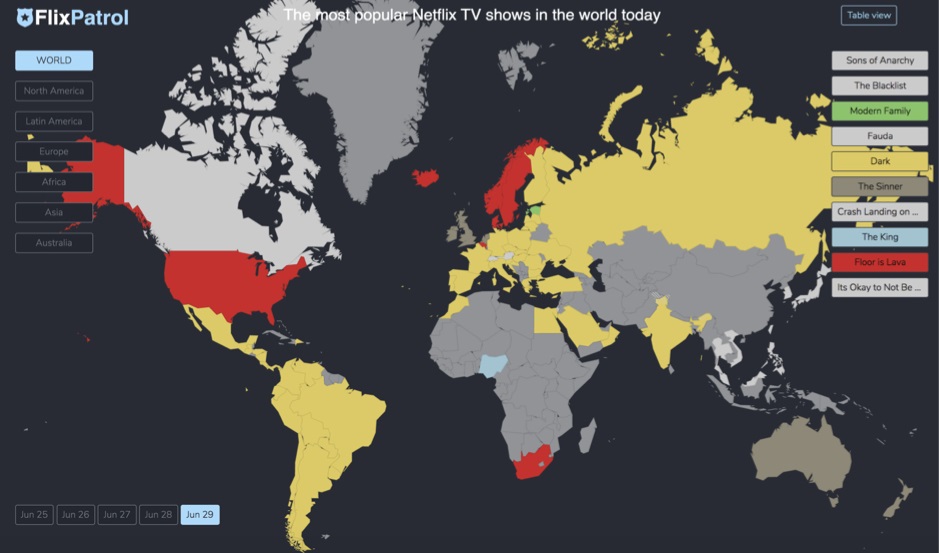

“Few recognize the extent to which Netflix has metamorphosed into a global television service. Unlike services that distribute only US-produced content, Netflix has funded the development of a growing library of series produced in more than 27 countries, across six continents, including Australia.

“Netflix has regional offices now in Singapore, Amsterdam, and São Paulo. Last year it opened its Australian headquarters in Sydney.”

Along with QUT’s Distinguished Professor Stuart Cunningham and Dr Ramon Lobato, Senior Research Fellow, RMIT, Professor Lotz is investigating the impact of global subscription video-on-demand platforms on national television markets.

“Internet-distributed video services such as Netflix, have completely transformed the entertainment landscape and the competitive field in which free-to-air television operates, as well as turned the definition of ‘pay TV’ on its head,” Professor Lotz said.

“But the Netflix model has been the real gamechanger. Previously, the core business of channels like the BBC, ABC or NBC that commission and pay the lion’s share of production fees for series has been nation bound, even if those shows would someday be available to audiences in many countries.

“Netflix’s propensity to commission series in multiple countries, and then make them available to the full 150-some million subscribers simultaneously, is unprecedented and something no television channel could do.

“A local example of this is Hannah Gadsby: Nanette which has given the Australian comedian a new global profile. She now has a second Netflix show - Hannah Gadsby: Douglas.

“And although many believe Netflix competes with the likes of Amazon Prime Video, Apple TV+, Stan and Disney+, none of these services show evidence of supporting multinational production at a scale comparable to Netflix.

“Our research project has compiled a database of series commissioned by Netflix (in whole or part) and their country of origin. We have found more than half of the titles are produced outside the US and initial analysis of Netflix original films suggests a similar pattern.”

However, Professor Lotz said Netflix could never develop the depth of content necessary to replace national providers, especially public service broadcasters central to cultural storytelling.

“It is difficult to appreciate whether some of Netflix’s peculiarity results from its global reach, business model, or distribution technology, but these are crucial questions to ask. And do these characteristics lead to the availability of stories, characters, and places not readily available? If so, this is a notable benefit to audiences,” she said.

“We should also ask how these characteristics affect opportunities available for writers, producers, and actors who might be rethinking the kind of stories that must be told to sell internationally.

“Appealing to audiences outside a commissioning channel’s country is increasingly necessary. Even if Netflix is unlikely to eliminate national providers, it is reconfiguring the competitive landscape.”

Professor Lotz also posted a blog series, Netflix 30 Q&A, in recent months that examines the differences of the SVOD business and how it allows Netflix different program strategies than linear, ad-supported channels.

“The long term and global rights the company seeks in its commissions have required significant changes in the remuneration norms for those who make its series, and it remains unclear whether the new norms amount to lower pay,” she said.

“National broadcasters worry about keeping up with the escalating fees Netflix can support for its prestige series’ and complain of an unfair playing field where Netflix isn’t subject to the same local content rules and other requirements.

“But business and cultural analysts must stop trying to shoehorn Netflix into the same category as linear channels and streaming services aimed at pushing US content abroad. Over its 23-year-existence, Netflix has evolved repeatedly. Perhaps this steady change fuels its misperception.”

Media contact:

Amanda Weaver, QUT Media, 07 3138 3151, amanda.weaver@qut.edu.au

After hours: Rose Trapnell, 0407 585 901, media@qut.edu.au