A simulator that trains robots must first be trained by the robot it’s required to train.

While this seems like a conundrum, QUT PhD researcher Jack Collins is solving it using motion capture technology to enhancing robotic performance.

“I work in the realm of ‘sim2real’ which looks to overcome a phenomenon called the ‘reality gap’,” Jack said.

“The problem is that if we teach a robot a new skill in a physics simulator and then transfer this new skill onto the real robot we don’t see the robot successfully perform the skill as we did in the simulator.

“An example of the reality gap might be if we teach a robot in simulation to pour drinks into glasses, it might be able to do this task 100% of the time in simulation but when we try to transfer this behaviour to a real robot it is only able to do the task 70% of the time.

“My research looks at how we can improve the real-world performance of the robot to something comparable to the simulator.”

Jack works under the supervision of QUT researchers Dr Ross Brown and Dr Juxi Leitner, who led the QUT-based winners of the international Amazon Robotics Challenge 2017, as well as David Howard from CSIRO Data61.

“We are trying to quantify the differences between the simulators and real-world using motion capture. We can use this information to improve the areas where simulators fail,” Jack said.

Jack records a robot doing tasks in the real world and investigates how to mirror this in simulators.

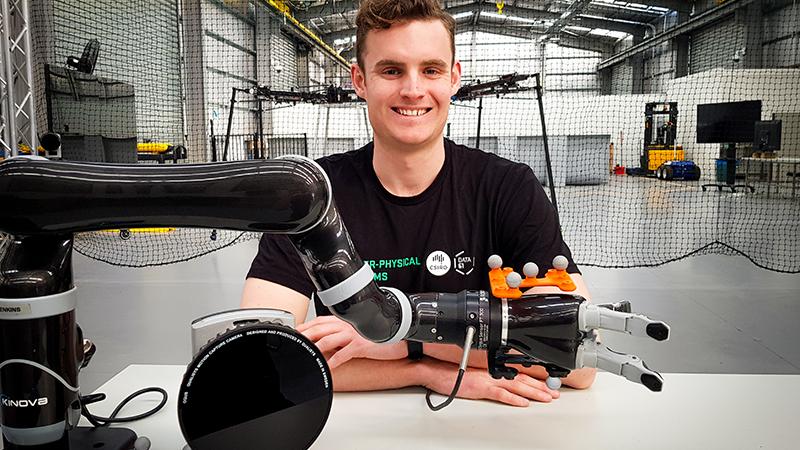

He uses the Kinova Mico2 - a robot arm with six joints and three-fingered gripper equipped with a Robotiq FT300 force sensor so it can perceive when it pushes on something.

Jack demonstrated the Kinova Mico2 robotic arm at Robotronica 2019 – QUT’s free robotics festival at the Gardens Point campus.

The arm is used in research and in assistive applications because it is comparatively cheap, lightweight, operates using mains power and is safe for interaction with people.

“We use the motion capture as a real-world ground truth that we compare to our simulation.

“We place reflective markers on the arm and track the movement of those markers in 3D space to a precision of less than one millimetre.

“We record the Kinova performing a range of tasks such as movements of the arm, the arm interacting with objects, the arm picking up and stacking objects.

“We then do the exact same movements in simulation and see if we can tune the simulator to mirror what we saw happen in the real world.”

Jack says there are lots of benefits to overcoming the reality gap and teaching robots in simulation rather than the real world.

“Teaching robots in simulation is safer, avoids breaking or damaging robots, and we can run simulations faster than real-time.

“We can also use robots in a simulation that we don’t have access to in the real world.”